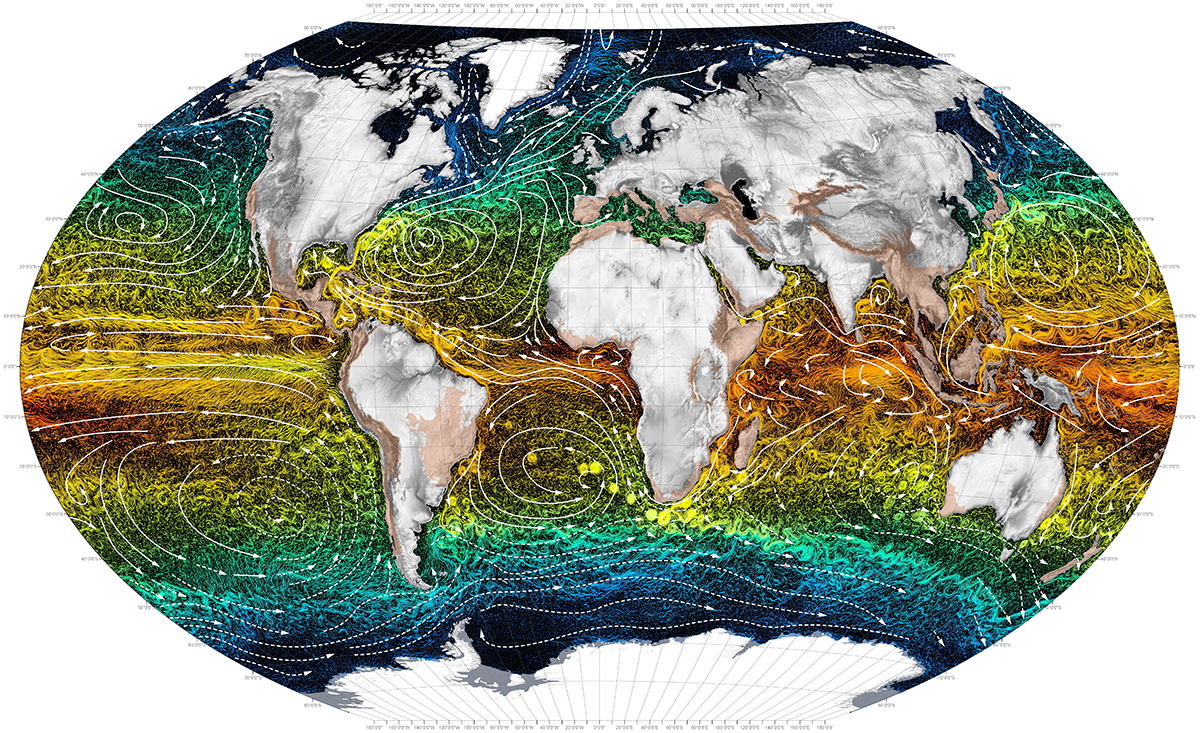

Ocean Currents. Photo by Atlas for the End of the World

The vast, mysterious ocean, covering 71 percent of the Earth, plays an essential role in our everyday lives. Not just for the coastal and island dwellers, but for everyone. The ocean provides many ecosystem services, including food production, fisheries, pharmaceuticals, oxygen regulation, carbon storage and sequestering, water quality enhancement, coastal protection, biodiversity, economy, cultural values, and climate and weather regulation. Without the ocean, we would not be able to survive.

One of the most critical ecosystem services of the ocean is weather and climate regulation because it affects economies and livelihoods on a global scale. The sea has a low albedo, meaning it absorbs most of the sun’s heat radiation. Thus, water molecules heat up and evaporate into the atmosphere and create storms that are carried over long distances by trade winds and currents. These storms can become destructive as they accumulate warm water while traveling over the ocean.

Ocean currents are crucial for regulating the climate and transferring heat around the globe. Water density, winds, tides, and the earth’s rotation direct and power the currents, which are found on the ocean’s surface and at a depth below 900 feet. They move water horizontally and vertically and occur on a local and global scale. The currents create a global conveyor belt that acts as a global circulation system. It transfers warm water and precipitation from the equator towards the cold-watered poles and vice versa. It also plays a vital role in distributing nutrients across the ocean.

As seasons change, so do wind and weather trends, sea surface temperatures, and currents. Currents are stronger in the winter than they are in the summer because there are stronger winds and colder sea temperatures. Furthermore, spring is a considerable transition period. During this time, temperatures begin to warm, the density and salinity of the ocean changes, and wind patterns shift. These factors significantly influence currents, causing them to become unstable.

Without currents, the land wouldn’t be habitable because temperatures would be too extreme; the equator too hot and the poles too cold. Additionally, the precipitation distributed by currents and wind is necessary to all living things and is needed to sustain life. Foreseeable current, weather, and climate trends are key components in maintaining a healthy economy by supporting crops, livestock, tourism, etc., and can also save lives from dangerous storms and create more resilient communities.

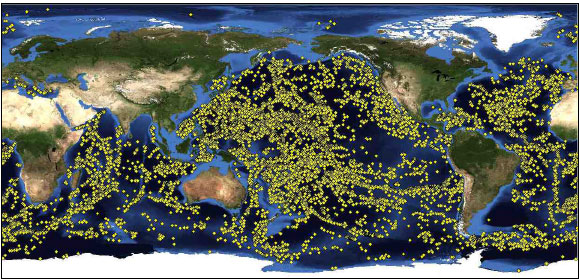

Currents are measured and monitored by moored and drifting buoys that relay data via satellite. These buoys are efficient in collecting data, but they are quite costly and require much effort to deploy, retrieve, and maintain. Moored buoys often break from their mooring and can't be implemented in deep waters. Wave Gliders, however, can measure and monitor surface currents on a local and global scale in any seas without the considerable exertion and cost. Therefore, they could be utilized as an alternative to some of the moored buoys or drifters while collecting other vital data such as salinity, sea surface temp, CO2 levels, and much more.

Europa has not experienced much trouble from the changing spring currents thus far. Although, on April 5th, she hit a robust northern current with no sea state to give her power, which made her veer off course a little. Fortunately, we were able to turn on the thruster (a small solar powered, electric propeller on the sub) that quickly put her back on track. We hope the currents remain steady and in our favor, so she’ll return home as soon as possible.